In any written language, words are subject to a triple association: sound, spelling and of course meaning. For example, the English word horse refers to the working and racing animal, is pronounced /hɔː(ɹ)s/ and spelled h-o-r-s-e. Anyone knowing how to read will be able to pronounce the word relatively correctly even if they have never seen it in writing before.

English is written in the Latin alphabetical script.

As explained by S. Dehaene, the reading process takes place here through the so-called phonological route: graphemes are mechanically converted into phonemes without resorting to deeper semantic representations.

The situation is quite different when it comes to Chinese

All Chinese languages are written in the unified system of Chinese characters. These Chinese characters are pronounced differently in each of the languages of the Chinese linguistic branch, for instance in Mandarin, the most widespread. Non-Chinese speakers often claim that the mapping of a Chinese character and its pronunciation is completely arbitrary; therefore it is said to be impossible to pronounce a character, even when knowing its meaning, unless its pronunciation has been learnt by rote beforehand.

The reality is slightly more subtle.

Indeed, it is often necessary to learn simultaneously a word’s character and its pronunciation

But it must be stressed that 80% to 90% of Chinese characters are actually compound characters. They often consist of at least two subcomponents: a phonetic root (there are about 200 of them) and a semantic root (there are about 1000 of them).

The phonetic root, often on the right side of the compound character, may give clues as to the pronunciation of the character.

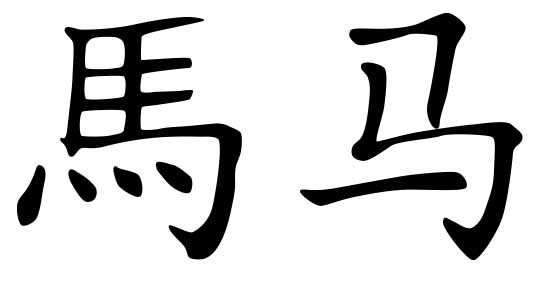

The semantic root, often on the left, tells about the word’s meaning, or at least the lexical category it belongs to. For instance, the Chinese character for a horse is马in simplified Chinese, and is pronounced mă (third tone) in Mandarin.

The word for mother is pronounced mā ma (ma is doubled, the first one is pronounced with the first tone); the compound character for each ma has the semantic root of woman on its left and the phonetic root of horse on its right.

In a paper dated 2007, Bao Guo Chen and colleagues proved that the more arbitrary the mapping between meaning and sound or spelling, the higher the effects of the Age of Acquisition (AoA) on Chinese reading (for native speakers). Characters acquired early would be read with ease; characters acquired at a later stage would be more difficult to read if the correspondence between writing and sound or spelling was difficult to predict.

In other words, the more difficult it is to deduct meaning and spelling by reading a character, the more detrimental late acquisition is to quality and speed of reading.

Thus, within Chinese language and for native speakers, the impact of the Age of Acquisition increases with the arbitrariness of the mapping between meaning, pronunciation and spelling. What is the situation for alphabetical languages? By definition, reading an alphabetical language gives a very valuable clue as to what the pronunciation is going to be*.

Taken as a whole, the Chinese language is significantly more arbitrary than alphabetical languages in terms of mapping from character to sound and meaning. One can therefore assume that for Chinese even more so than for other languages, there is benefit in learning the language early so as not to be negatively impacted by the enhanced effects of the Age of Acquisition on reading.

To learn more about Chinese learning :

Chen, B. G., Zhou, H. X., Dunlap, S. and Perfetti, C. A. (2007).Age of acquisition effects in reading Chinese: Evidence in favour of the arbitrary mapping hypothesis. British Journal of Psychology, 98: 499–516. doi: 10.1348/000712606X165484

Stanislas Dehaene (2007). Les neurones de la lecture. Editions Odile Jacob

Note : * The situation varies quite significantly from language to language. Italian or Turkish, for instance, are very easy to pronounce when reading a text, while a given spelling in English can be read in multiple ways (refer for instance to tough, through, thorough, etc…)